Reading time: 8 minutes

This article focuses on the subject of the secularisation of church buildings, meaning they lose their sacred status and are repurposed for secular use, or alternatively, the altered utilisation of ecclesiastical buildings, examining the various regional approaches in different countries. While the process of secularisation is often formally regulated by church and state institutions, the cultural and social implications vary greatly. How former places of worship are dealt with is closely linked to regional identities, religious traditions, and social debates – and it is precisely this diversity that makes the topic so fascinating.

Causes and Significance of Secularisation

The decline in religious practice in Europe, especially within Christianity, has for decades meant that numerous church buildings stand empty and can no longer be used for their original purpose. The reasons are manifold: demographic changes, urbanisation, secularisation, but also financial burdens for the congregations. From a theological perspective, each secularisation must be marked by a special act, often accompanied by a ritual that signifies the deconsecration of the building. Through secularisation, the church becomes a civic object, which may henceforth serve secular purposes.

Regional Differences and National Particularities

The manner in which church buildings are secularised and repurposed differs significantly between countries and regions. In some countries the process is highly formalised, in others decisions are made more pragmatically and situationally. Europe in particular demonstrates a wide range of approaches, from preservation as cultural monuments to conversion into social institutions, museums, or even private residences.

Germany

In Germany, the secularisation of church buildings is often accompanied by intense social debates and emotional discussions. The Protestant and Catholic churches have detailed regulations on how deconsecration should take place. Former churches are frequently converted into cultural centres, libraries, or event venues. A well-known example is the Johanneskirche in Düsseldorf, which, following its secularisation, is now used as a cultural church and provides space for concerts, exhibitions, and social projects.

Netherlands

The Netherlands are known for their pragmatic approach. Given a particularly sharp decline in church attendance, many places of worship have been secularised and repurposed in diverse ways. For instance, the Dominican Church in Maastricht was transformed into a bookshop, now considered an outstanding architectural example of successful repurposing. In Utrecht, a church became a restaurant and event space, enriching the local cultural scene.

United Kingdom

Secularisation of church buildings is also a much-discussed topic in the United Kingdom. The Church of England has developed its own procedure for deconsecration and repurposing. Many churches have been turned into art galleries, cafés, or even climbing centres. A prominent example is St. Luke’s Church in London, which today serves as a concert hall, skilfully combining historic architecture with modern use.

France

In France, the subject is caught between state monument protection and church tradition. As many church buildings are state-owned, repurposing often takes place in close coordination with regional authorities. In Paris, for example, Église Saint-Eustache was opened as a venue for festivals following its secularisation, with special attention paid to preserving its historic substance.

Scandinavia

The Scandinavian countries have found their own ways of dealing with secularisation. In Denmark, for instance, many churches are used as community centres or libraries after deconsecration. In Norway, a former church now serves as a centre for refugee aid and social work, illustrating the connection between religious heritage and contemporary social engagement.

Global Perspectives and Cultural Implications

There are also interesting examples of church secularisation outside Europe. In the USA, former places of worship are frequently converted into homes or offices, often preserving their architectural character. In South America, some churches serve as music schools or art centres after secularisation, thus helping to strengthen local communities.

Each of these examples shows that the secularisation of church buildings is much more than a structural or legal act. It reflects social change and creates space for new forms of community, culture, and social interaction.

Architectural and Heritage Conservation Challenges in Repurposing and Redesign

In many regions of the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, a decline in membership among numerous congregations can be observed, partly due to demographic changes. This process has intensified in recent years.

As a result, there is a significant surplus of existing building space at both the parish and deanery level. This includes meeting rooms in parish halls and the community centres of the 1950s and 1960s, as well as vicarages that are no longer needed due to changes in the allocation of ministerial posts. There are also buildings for which renovation is no longer economically viable due to accumulated maintenance needs. High operating costs and necessary building maintenance measures pose financial challenges for many congregations.

For these reasons, congregations are engaging with their future development and considering possible mergers or cooperations, which also involves evaluating their existing building stock. In 2022, the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau adopted regulations for building requirements and development planning. Congregations are also reorganising themselves into so-called neighbourhood spaces. Since 2022, all buildings in these spaces have been reviewed and categorised into A, B and C during workshops. Category A buildings, which are to be retained for the long term, are slated for quality improvements, such as energy-efficient modernisation or measures to improve accessibility. Depending on the outcome of the assessment, this may also include functional expansion and renovation of churches so that they can accommodate uses beyond worship.

Acceptance in Congregations, Dealing with Identity and History

The building requirements and development plan is essentially a participatory process. The congregations are involved at various stages, such as site visits in neighbourhood spaces as a first step, but also in workshops. There, three prepared options are presented and discussed, and the neighbourhood space can continue to work on the options and contribute its own ideas in group sessions, always with the aim of meeting the specified guidelines. The process leads to changes in the building stock, as Category C buildings are no longer subsidised collectively by the church. The main focus is on parish halls, which have a significant surplus of meeting space at the church-wide level.

The process becomes challenging when congregations in newly formed neighbourhood spaces continue to pursue primarily their own interests, and there is strong “localism”. This often leads to individual buildings being prioritised over those of other congregations in building processes. Especially older congregation members often find it difficult to accept necessary changes due to emotional attachment to existing buildings. Overall, however, the need to make changes and reduce building stock is now recognised by the majority of those involved.

Concept ‘Church Can Do More’ as a Counterproposal to Secularisation

A church serves not only for Sunday worship, but can also be open on weekdays. Church spaces are frequently used as parish halls or as venues for concerts, youth theatre, and similar events.

The motto ‚Church can do more’, coined by Margrit Schulz, Director of Church Architecture at the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, refers to future changes in the way church buildings are managed. These buildings are currently being reviewed. Most churches are to be preserved and made more attractive through a range of measures: accessible, open to diverse event formats, available for quiet reflection and prayer, suitable for celebrations and people of different generations, and open to social services. Art and architecture are also taken into account.

Within the framework of the “Church can do more” concept, the aim is to link various uses of sacred spaces. Additional uses can take place within, on, or next to church buildings.

Churches are buildings with high visibility and social significance in the Protestant church. The goal is to achieve the highest possible utilisation of these buildings in order to preserve them as religious spaces in the long term. Additional parish or public functions shared with municipalities and other third parties are also being considered.

Possible additional uses include the installation of secular meeting rooms by partitioning off under galleries or with separate areas that allow appropriate temperature control of occupied spaces without affecting the organ or building physics.

Projects: Context, Analysis, and Execution

Evangelical Lutheran Parish of Rüsselsheim

As early as 2012, a building development study was commissioned for the Evangelical Church Parish Association in Rüsselsheim. It became clear at that time that the number of existing buildings could not be maintained in the long term in view of the marked decline in congregation members. The aim of the study was therefore, taking into account all buildings present at the time, to examine the building stock in several scenarios in terms of usage, costs, and development opportunities, and on this basis to carry out a process of concentration including a reduction of the building stock. Since then, the building stock has been significantly reduced; selected sites saw partial demolition of existing buildings, plots sold off, and the remaining stock enriched in quality.

Following the building development study, the site of the Luther Church, built in the 1950s, was to be further developed. Planning and implementation arose from an expert procedure involving several architectural firms. Large parts of the existing plot, including the parish hall, vicarage, sexton’s flat, office wing and nursery, were handed over to an investor from the church sector. The church itself was reinforced, the interior divided into two levels, extensively renovated, with new assembly areas on the ground floor and a sacred space in the newly created upper floor. Administrative areas were accommodated in a side extension.

As part of a building-specific development plan change, a new nursery and student residence were built on the sold-off plot. The realignment of the buildings and the administration wing has made the square in front of the buildings more clearly defined in urban planning terms. The church, which is listed, was partially renovated on the exterior. The site serves not only the Luther Church congregation for gatherings and worship, but is also available to the neighbouring Martins Church congregation (where assembly areas were downsized). The administration wing is intended to serve the joint administration of several congregations in the long term.

During the construction phase, the church council contributed wherever possible, clearing the church, dismantling the organ, and planting the outdoor areas themselves. According to the pastor, this was a key factor in acceptance of the redesigned church and the use of the new assembly areas, and also greatly strengthened the cohesion of those involved.

The assembly areas and foyer on the ground floor are technically independent and separately heated, and are partly completely detached from the outer walls of the building. The sacred space and the ground floor areas outside the assembly areas are not thermally separated, so the previous sacred space can still be experienced.

Plans: Soan Architekten Bochum, Photos ©Roman Weis Fotografie Essen

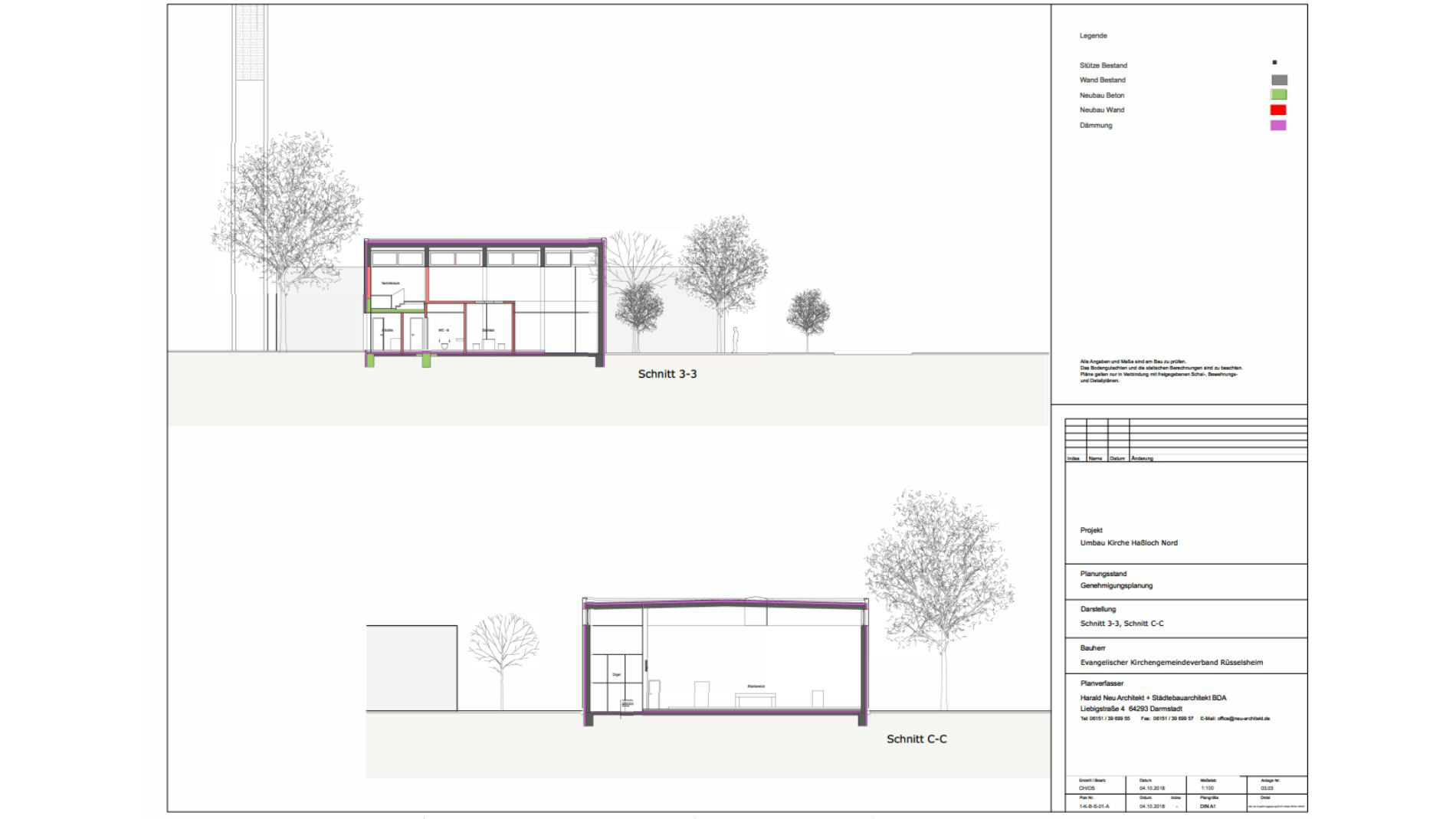

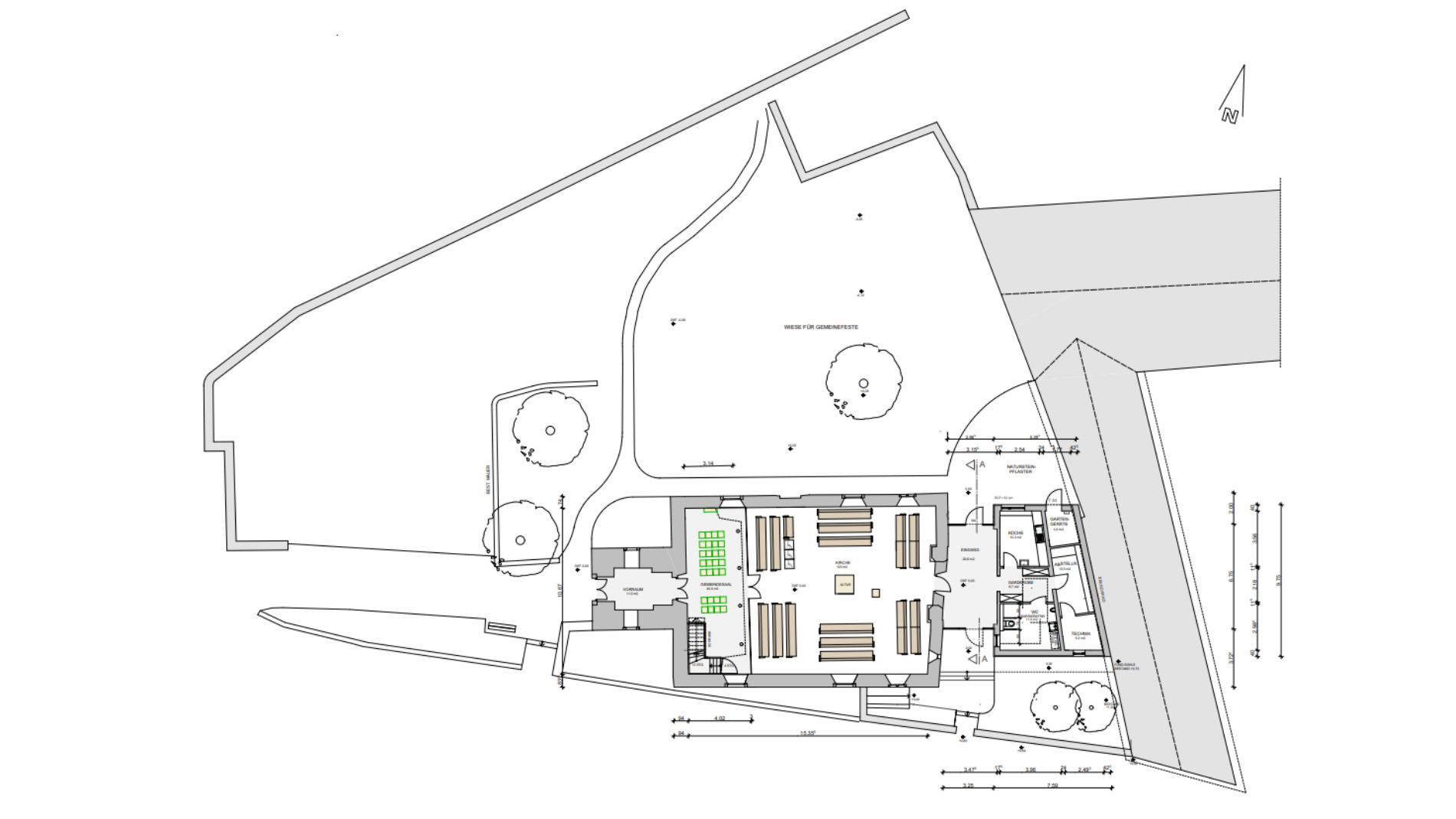

Converted Church of the Bonhoeffer Parish in Haßloch-Nord (Rüsselsheim)

Following the preliminary building development concept in Rüsselsheim, this location was analysed in detail. The reason for the measures taken was the merger of two church congregations and the associated search for a suitable site for a joint centre. As these plans could not be realised, a feasibility study was conducted to examine how the site of the former Evangelical Reconciliation Church congregation could meet current requirements. This included reviewing the reduction of areas as well as the development and sale of unused sections of land, with consideration given to the mandate to create social housing.

Of the original community centre with church, assembly rooms, parish flat, as well as sacristan’s and sister’s flats, only the sacred space was preserved. This was remodelled so that a foyer with access to an upper gallery, intended for future use as an assembly room, was created. Sanitary facilities and a kitchenette were incorporated to enable versatile use of the sacred space and the gallery.

The church building was equipped with a brine heat pump and a photovoltaic system, thus ensuring CO₂-neutral operation.

Plans: Harald Neu Architekten BDA, Darmstadt, Photos: ©Thomas Ott, Mühltal

In addition to the two projects presented here, several other smaller churches in Rheinhessen were upgraded as part of the "Church Can Do More" initiative. In all cases, the existing parish halls, which were often oversized and had become outdated, were sold. Parish life now takes place together with the Sunday service in the churches that have been converted accordingly. One further example is presented here by way of illustration:

Flomborn

Conversion and interior renovation of the late Baroque church as well as an extension with a functional annex including a kitchen. The former chancel area has been transformed into an entrance area with access to the annex; the space beneath the gallery has been separated from the nave by a glass wall, making it well suited for parish work and smaller events. In the sanctuary, the pews have been newly arranged around the altar. The existing lighting has been renewed.

Plans: Jaberg Architekten, Gundersheim, Photos: © Referat kirchliches Bauen der EKHN

Conclusion

The article examines the secularisation of church buildings as part of societal change, with regionally diverse approaches, particularly in Europe. Using the example of the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, it illustrates how concepts such as "Church Can Do More" and specific renovation projects are preserving and redesigning sacred buildings for modern, multifunctional uses.

This article was written by the Church Building Department of the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau

bauen.ekhn.de